BLUE/PURPLE VASCULAR LESIONS

Hemangioma Varix Angiosarcoma Kaposi’s Sarcoma Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia

▼ BROWN MELANOTIC LESIONS

Ephelis and Oral Melanotic Macule Nevocellular Nevus and Blue Nevus Malignant Melanoma Drug-Induced Melanosis Physiologic Pigmentation Café au Lait Pigmentation Smoker’s Melanosis Pigmented Lichen Planus Endocrinopathic Pigmentation HIV Oral Melanosis Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

Hemangioma Varix Angiosarcoma Kaposi’s Sarcoma Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia

▼ BROWN MELANOTIC LESIONS

Ephelis and Oral Melanotic Macule Nevocellular Nevus and Blue Nevus Malignant Melanoma Drug-Induced Melanosis Physiologic Pigmentation Café au Lait Pigmentation Smoker’s Melanosis Pigmented Lichen Planus Endocrinopathic Pigmentation HIV Oral Melanosis Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

▼ BROWN HEME-ASSOCIATED LESIONS

Ecchymosis Petechia Hemochromatosis

▼ GRAY/BLACK PIGMENTATIONS

Amalgam Tattoo Graphite Tattoo Hairy Tongue Pigmentation Related to Heavy-Metal Ingestion

▼ SUMMARY

In the course of disease, the mucosal tissues can assume a variety of discolorations. Disease processes can culminate in the formation of pseudomembranes, in increased keratinization (white lesions), or in increased vascularization (red lesions). Blue, brown, and black discolorations constitute the pigmented lesions of the oral mucosa, and such color changes can be attributed to the deposition of either endogenous or exogenous pigments. Although there are many biochemical substances and metabolic products that are pigmented, only a few become deposited in the oral soft tissues although some accumulate in developing dentin during odontogenesis (eg, bilirubin pigment, porphyrins, and hemosiderin).

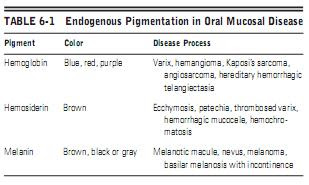

The endogenous pigmentation of the oral mucous membrane is most often explained by the presence of hemoglobin, hemosiderin, and melanin (Table 6-1). Hemoglobin imparts a red or blue appearance to the mucosa and represents pigmentation associated with vascular lesions; the coloration is rendered by circulating erythrocytes coursing through patent vessels. In contrast, hemosiderin appears brown and is deposited as a consequence of blood extravasation, which may occur as a consequence of trauma or a defect in hemostatic mechanisms. Hemochromatosis (generalized hemosiderin tissue deposition) may occur as a result of a variety of pathologic states.

Melanin is the pigment derivative of tyrosine and is synthesized in melanocytes, which subsequently transfer the melanin granules into adjacent basal cells to protect against the damaging effects of actinic irradiation. An increase in melanin pigment occurs when melanocytes oversynthesize or overpopulate. Overproduction (basilar melanosis) may be caused by a variety of mechanisms, including increased sun exposure, drugs, the pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and genetic factors (in association with certain syndromes). Melanocyte overpopulation occurs in benign nevi and in malignant melanomas.

The endogenous pigmentation of the oral mucous membrane is most often explained by the presence of hemoglobin, hemosiderin, and melanin (Table 6-1). Hemoglobin imparts a red or blue appearance to the mucosa and represents pigmentation associated with vascular lesions; the coloration is rendered by circulating erythrocytes coursing through patent vessels. In contrast, hemosiderin appears brown and is deposited as a consequence of blood extravasation, which may occur as a consequence of trauma or a defect in hemostatic mechanisms. Hemochromatosis (generalized hemosiderin tissue deposition) may occur as a result of a variety of pathologic states.

Melanin is the pigment derivative of tyrosine and is synthesized in melanocytes, which subsequently transfer the melanin granules into adjacent basal cells to protect against the damaging effects of actinic irradiation. An increase in melanin pigment occurs when melanocytes oversynthesize or overpopulate. Overproduction (basilar melanosis) may be caused by a variety of mechanisms, including increased sun exposure, drugs, the pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and genetic factors (in association with certain syndromes). Melanocyte overpopulation occurs in benign nevi and in malignant melanomas.

The distribution of these various pigments in the oral mucosa is quite variable, ranging from a focal macule to broad diffuse tumefactions. The specific coloration, tint, location, multiplicity, size, and configuration of the pigmented lesion(s) are of diagnostic importance.

Exogenous pigments are usually traumatically deposited directly into the submucosa. However, some may be ingested, absorbed, and distributed hematogenously, to be precipitated in connective tissues, particularly in areas subject to chronic inflammation, such as the gingiva (Table 6-2). In the past, various metallic compounds were used medicinally, but currently, this therapy is rarely prescribed. For that reason, lesions attributable to heavy-metal therapy are no longer seen, with the exception of lesions caused by gold, which is still used systemically to treat arthritis. Lastly, exogenous pigment may be generated by chromogenic bacteria that colonize the keratinized surface of the tongue (hairy tongue).

In this chapter, the differential diagnosis of oral pigmentation is organized according to color, configuration, and distribution (Table 6-3).

Exogenous pigments are usually traumatically deposited directly into the submucosa. However, some may be ingested, absorbed, and distributed hematogenously, to be precipitated in connective tissues, particularly in areas subject to chronic inflammation, such as the gingiva (Table 6-2). In the past, various metallic compounds were used medicinally, but currently, this therapy is rarely prescribed. For that reason, lesions attributable to heavy-metal therapy are no longer seen, with the exception of lesions caused by gold, which is still used systemically to treat arthritis. Lastly, exogenous pigment may be generated by chromogenic bacteria that colonize the keratinized surface of the tongue (hairy tongue).

In this chapter, the differential diagnosis of oral pigmentation is organized according to color, configuration, and distribution (Table 6-3).