CYSTS OF THE JAWS AND BENIGN ODONTOGENIC TUMORS

Cysts of the Jaw

Cysts (ie, fluid-filled epithelial-lined cavities in the jaw bones and soft tissues of the face, floor of the mouth, and neck) may cause either intraoral or extraoral swellings that may clinically

Cysts of the Jaw

Cysts (ie, fluid-filled epithelial-lined cavities in the jaw bones and soft tissues of the face, floor of the mouth, and neck) may cause either intraoral or extraoral swellings that may clinically

resemble a benign tumor.Unilocular and multilocular radiolucencies discovered in the jaw bones by radiographic examination must also be differentiated from solid growths in the jaw, a distinction that cannot always be made by inspecting the radiograph. However, the majority of cysts are small, do not distend surface tissues, and are often first recognized in routine dental radiographic examinations.Others are discovered during investigation of a nonvital tooth or an acute dental abscess due to secondary infection of the cyst or by loosening of the teeth and by jaw fracture. Small isolated radiolucencies in the jaw bone that are not associated with a loss of pulp vitality are usually observed over several months for increase in size before surgical exploration. Radiolucencies that are suspected of being cysts or tumors and that are not associated with a necrotic tooth require biopsy.

Radiographic examination rarely provides a conclusive diagnosis as to the nature of a radiolucency in the jaw although it may be used to gauge the rate of growth of such lesions and to detect erosion of tooth roots and cortical destruction. These features are characteristic of aggressive benign lesions as well as malignant lesions. Contrary to traditional lore, there is no size range that separates periapical cysts from dental granulo-

Radiographic examination rarely provides a conclusive diagnosis as to the nature of a radiolucency in the jaw although it may be used to gauge the rate of growth of such lesions and to detect erosion of tooth roots and cortical destruction. These features are characteristic of aggressive benign lesions as well as malignant lesions. Contrary to traditional lore, there is no size range that separates periapical cysts from dental granulo-

mas, and microscopic examination of periapical lesions frequently reveals tiny cystic areas and areas of epithelial proliferation in what is clinically thought to be a granuloma. Similarly, caution must be used in diagnosing even large radiolucent jaw lesions as cysts simply because they appear “spherical” on the radiograph. The differential diagnosis of multiple radiolucencies in the jaw should include consideration of multiple myeloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, metastatic carcinoma, giant cell granuloma and hyperparathyroidism, multiple dental granulomas, periapical cysts, cemental dysplasia, ossifying fibroma, and fibrous dysplasia. Microscopic examination of the cyst wall provides the clear diagnosis that is important to the management of the lesion, and submission of all excised tissue (including fragments scraped from the wall of the jaw cyst and periapical tissues curetted at the time of dental extraction or apicoectomy) for histopathologic examination is strongly urged.

The treatment of choice for a cyst is local excision with complete removal of the cyst lining.With larger lesions, the surgeon may decide to curet the lining through a relatively small window; removal of the lining can be expected to be incomplete, with recurrence a possibility. Alternatively, the lining of larger cysts may be sutured to the oral mucosa adjacent to the surgically created window, and the cyst may be “marsupialized.” If such a lesion is kept patent by repeated irrigation, it will cease to expand, it will not become secondarily infected, and the defect in the jaw will gradually even out.

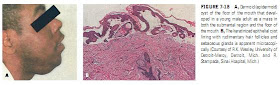

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to include detailed discussion of the clinical, radiographic, and histologic features of each of the different types of cysts that affect the jaws and adjacent oral tissues. The reader is referred to the more extensive coverage provided in most textbooks of oral pathology and oral radiology,FIGURE 7-18 A, Dermoid (epidermoid) cyst of the floor of the mouth that developed in a young male adult as a mass in both the submental region and the floor of the mouth. B, The keratinized epithelial cyst lining with rudimentary hair follicles and sebaceous glands is apparent microscopically. (Courtesy of R.K. Wesley, University of Detroit-Mercy, Detroit, Mich. and R. Stampada, Sinai Hospital, Mich.)

as well as to articles that review particular classes of cysts.The radiographic appearance of some odontogenic and non-odontogenic cysts is illustrated in Figures 7-20, 7-21, and 7-22. The 1971 World Health Organization (WHO) classification (also the 1992 revision)of epithelial jaw cysts, which distinguishes cysts arising from the tooth germ tissues (odontogenic cysts) from those of non-odontogenic origin and also distinguishes cysts that represent an inflammatory process from those that arise “autonomously,” remains the generally accepted classification. Minor revisions of this classification were pro-

The treatment of choice for a cyst is local excision with complete removal of the cyst lining.With larger lesions, the surgeon may decide to curet the lining through a relatively small window; removal of the lining can be expected to be incomplete, with recurrence a possibility. Alternatively, the lining of larger cysts may be sutured to the oral mucosa adjacent to the surgically created window, and the cyst may be “marsupialized.” If such a lesion is kept patent by repeated irrigation, it will cease to expand, it will not become secondarily infected, and the defect in the jaw will gradually even out.

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to include detailed discussion of the clinical, radiographic, and histologic features of each of the different types of cysts that affect the jaws and adjacent oral tissues. The reader is referred to the more extensive coverage provided in most textbooks of oral pathology and oral radiology,FIGURE 7-18 A, Dermoid (epidermoid) cyst of the floor of the mouth that developed in a young male adult as a mass in both the submental region and the floor of the mouth. B, The keratinized epithelial cyst lining with rudimentary hair follicles and sebaceous glands is apparent microscopically. (Courtesy of R.K. Wesley, University of Detroit-Mercy, Detroit, Mich. and R. Stampada, Sinai Hospital, Mich.)

as well as to articles that review particular classes of cysts.The radiographic appearance of some odontogenic and non-odontogenic cysts is illustrated in Figures 7-20, 7-21, and 7-22. The 1971 World Health Organization (WHO) classification (also the 1992 revision)of epithelial jaw cysts, which distinguishes cysts arising from the tooth germ tissues (odontogenic cysts) from those of non-odontogenic origin and also distinguishes cysts that represent an inflammatory process from those that arise “autonomously,” remains the generally accepted classification. Minor revisions of this classification were pro-

posed by Main and Shear in 1985. Main’s revision of the WHO classification is presented in Table 7-1. Four types of cyst (follicular or dentigerous, nasopalatine, radicular, and keratocyst) constitute 95% of all epithelial jaw cysts and are frequently those that attain considerable size before they are recognized.

The follicular (or dentigerous) cyst arises from the reduced enamel epithelium of the dental follicle of an unerupted tooth, which may be part of the regular dentition or a supernumerary, and remains attached to the neck of the tooth, enclosing the crown within the cyst. Some unerupted teeth appear to be more susceptible than others to the development of such cysts (eg, third molars and canines). Studies with tooth germ isografts in the hamster cheek pouch and clinical observations suggest a correlation between cystic degeneration of the tooth follicle and enamel hypoplasia.In addition to their potential for attaining large size, follicular cysts are noteworthy for their tendency to resorb the roots of adjacent teeth,

and for the occasional development of neoplastic changes such as plexiform ameloblastoma and carcinoma within an isolated segment of the cyst wall. This potential for neoplastic change and infiltration beyond the cyst wall and the occasional finding of other odontogenic tumors in association with a follicular cyst fully justify the need for histopathologic examination of all material derived from jaw cysts.

The follicular (or dentigerous) cyst arises from the reduced enamel epithelium of the dental follicle of an unerupted tooth, which may be part of the regular dentition or a supernumerary, and remains attached to the neck of the tooth, enclosing the crown within the cyst. Some unerupted teeth appear to be more susceptible than others to the development of such cysts (eg, third molars and canines). Studies with tooth germ isografts in the hamster cheek pouch and clinical observations suggest a correlation between cystic degeneration of the tooth follicle and enamel hypoplasia.In addition to their potential for attaining large size, follicular cysts are noteworthy for their tendency to resorb the roots of adjacent teeth,

and for the occasional development of neoplastic changes such as plexiform ameloblastoma and carcinoma within an isolated segment of the cyst wall. This potential for neoplastic change and infiltration beyond the cyst wall and the occasional finding of other odontogenic tumors in association with a follicular cyst fully justify the need for histopathologic examination of all material derived from jaw cysts.

The eruption cyst is the soft-tissue analogue of the follicular cyst; it presents clinically as a bluish gray swelling of the mucosa over an erupting tooth and has been characterized as a “cyst arising within the oral mucosa by the separation of the follicle from around the anatomical crown of an erupting tooth.”Excision of a wedge of the mucosa to expose the tooth crown is usually adequate.

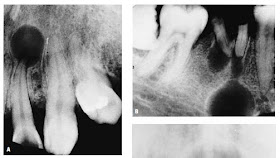

Radicular cysts (see Figure 7-21, A and B) derive from inflammatory proliferation and cystic degeneration of epithelial cell Malassez rests contained in periapical granulomatous tissue, usually secondary to pulp necrosis. When this change occurs in a granuloma that has not been eliminated by tooth extraction, the cyst is no longer associated with the apex of a tooth and is customarily referred to as a residual cyst. Radicular cysts are the most frequent type of jaw cyst and make up as much as 55% of jaw cysts in some series (once again, the difficulties of determining if a given radiolucency is a cyst, a granuloma, or some other lesion influence the validity of the estimates given for different series). There is a large body of literature devoted to elucidating the mechanism and cause of the epithelial proliferation, fluid accumulation, bone resorption, and expansion that underlie the development of radicular cysts.The odontogenic keratocyst (formerly, primordial cyst)(Figures 7-23 and 7-24; see also Figure 7-20, B, and

Radicular cysts (see Figure 7-21, A and B) derive from inflammatory proliferation and cystic degeneration of epithelial cell Malassez rests contained in periapical granulomatous tissue, usually secondary to pulp necrosis. When this change occurs in a granuloma that has not been eliminated by tooth extraction, the cyst is no longer associated with the apex of a tooth and is customarily referred to as a residual cyst. Radicular cysts are the most frequent type of jaw cyst and make up as much as 55% of jaw cysts in some series (once again, the difficulties of determining if a given radiolucency is a cyst, a granuloma, or some other lesion influence the validity of the estimates given for different series). There is a large body of literature devoted to elucidating the mechanism and cause of the epithelial proliferation, fluid accumulation, bone resorption, and expansion that underlie the development of radicular cysts.The odontogenic keratocyst (formerly, primordial cyst)(Figures 7-23 and 7-24; see also Figure 7-20, B, and

Figure 7-22), which arises from reduced enamel epithelium, dental lamina rests, and Malassez rests, are of considerable interest because of their tendency for recurrence after initial surgical intervention.Keratocysts are characterized by keratinization and budding cyst lining. This cyst occurs as an isolated finding and in association with other basal cell cancers and various other lesions in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (see “Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome,” below).

The nasopalatine (incisive canal) cyst (see Figure 7-21, D) is derived from remnants of epithelium-lined vestigial oronasal duct tissue and possibly also from Jacobson’s (vomeronasal) organ, which is said to account for the occasional finding of pigmented cells in the wall of these cysts. On the basis of radiographic surveys of dried skulls, the frequency of this cyst has been described as being as high as 1.8% although differences of opinion as to the maximum size the image of the incisive canal may attain without being considered cystic raise doubt as to the validity of this figure.The surgical removal of a nasopalatine cyst commonly produces loss of sensation and paresthesia of the anterior palate supplied by the nasopalatine nerve; thus, unequivocal signs of cystic swelling in the canal are required before exploration of the area or excision of a suspected cyst is undertaken.

Cysts of the maxillary sinus (see Figure 7-21, C) were thought to arise from pseudostratified columnar respiratorytype epithelium rather than from the oral mucosa, but they are of interest because of the frequency (as high as 2.6% in one series)with which they are recognized in panoramic dental radiographs, which demonstrate them more efficiently than the traditional Waters’ projection.In reality, most of these dome-shaped radiopacities of the sinus floor are nothing more than inflammatory polyps and are not true “retention” cysts. Cysts and odontogenic tumors arising in the maxilla, especially molar and premolar radicular cysts, may extend into the maxillary sinus but usually do so by expanding the floor of the sinus ahead of them.Cystic degeneration may also occur in benign odontogenic tumors, but the hamartomatous or neoplastic nature of odontogenic tumors requires that they be given special consideration (see following section). The misleading socalled cystic radiographic appearance of many odontogenic tumors (reflected in the synonym “multilocular cyst” for ameloblastoma), the majority of which develop within and expand the jaw, has also led to clinical confusion between the two classes of lesions.Cystic degeneration is a common change in odontogenic tissue, and it is not surprising that odontogenic tumors frequently contain cystic areas. The importance of a thorough histopathologic examination of all curetted material is once again underlined by the fact that tumor tissue may be recognized in only a small section of a lesion, the bulk of which is represented by a relatively nonspecific odontogenic cyst.

Cysts of the maxillary sinus (see Figure 7-21, C) were thought to arise from pseudostratified columnar respiratorytype epithelium rather than from the oral mucosa, but they are of interest because of the frequency (as high as 2.6% in one series)with which they are recognized in panoramic dental radiographs, which demonstrate them more efficiently than the traditional Waters’ projection.In reality, most of these dome-shaped radiopacities of the sinus floor are nothing more than inflammatory polyps and are not true “retention” cysts. Cysts and odontogenic tumors arising in the maxilla, especially molar and premolar radicular cysts, may extend into the maxillary sinus but usually do so by expanding the floor of the sinus ahead of them.Cystic degeneration may also occur in benign odontogenic tumors, but the hamartomatous or neoplastic nature of odontogenic tumors requires that they be given special consideration (see following section). The misleading socalled cystic radiographic appearance of many odontogenic tumors (reflected in the synonym “multilocular cyst” for ameloblastoma), the majority of which develop within and expand the jaw, has also led to clinical confusion between the two classes of lesions.Cystic degeneration is a common change in odontogenic tissue, and it is not surprising that odontogenic tumors frequently contain cystic areas. The importance of a thorough histopathologic examination of all curetted material is once again underlined by the fact that tumor tissue may be recognized in only a small section of a lesion, the bulk of which is represented by a relatively nonspecific odontogenic cyst.