Leukoplakia is a white oral precancerous lesion with a recognizable risk for malignant transformation. In 1972, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined a precancerous lesion as a “morphologically altered tissue in which cancer is more likely to occur than in its apparently normal counterpart.”

The most commonly encountered and accepted precancerous lesions in the oral cavity are leukoplakia and erythroplakia. Leukoplakia is currently defined as “a white patch or plaque that cannot be characterized clinically or pathologically as any other disease” (WHO, 1978).This definition has no histologic connotation and is used strictly as a clinical description. The risk of malignant transformation varies according to the histologic and clinical presentation, but the total lifetime risk of malignant transformation is estimated to be 4 to 6%.

Etiology

A number of locally acting etiologic agents, including tobacco, alcohol, candidiasis, electrogalvanic reactions, and (possibly) herpes simplex and papillomaviruses, have been implicated as causative factors for leukoplakia. True leukoplakia is most often related to tobacco usage;more than 80% of patients with leukoplakia are smokers. The development of leukoplakia in smokers also depends on dose and on duration of use, as shown by heavier smokers’ having a more frequent incidence of lesions than light smokers. Cessation of smoking often results in partial to total resolution of leukoplakic lesions. Smokeless tobacco is also a well-established etiologic factor for the development of leukoplakia; however, the malignant transformation potential of smokeless tobacco–induced lesions is much lower than that of smoking-induced lesions.

Alcohol consumption alone is not associated with an increased risk of developing leukoplakia, but alcohol is thought to serve as a promoter that exhibits a strong synergistic effect with tobacco, relative to the development of leukoplakia and oral cancer.In addition to tobacco, several other etiologic agents are associated with leukoplakia. Sunlight (specifically, ultraviolet radiation) is well known to be an etiologic factor for the formation of leukoplakia of the vermilion border of the lower lip.Candida albicans is frequently found in histologic sections of leukoplakia and is consistently (60% of cases) identified in nodular leukoplakias but rarely (3%) in homogeneous leukoplakias. The terms “candidal leukoplakia” and “hyperplastic candidiasis” have been used to describe such lesions.

Whether Candida constitutes a cofactor either for excess production of keratin or for dysplastic or malignant transformation is unknown(see previous section on candidiasis). Human papillomavirus (HPV), particularly subtypes HPV-16 and HPV-18, have been identified in some oral leukoplakias. The role of this virus remains questionable, but there is evidence that HPV-16 may be associated with an increased risk of malignant transformation.Of interest, there is some evidence that oral leukoplakia in nonsmokers has a greater risk for malignant transformation than oral leukoplakia in smokers.

Clinical Features

The incidence of leukoplakia varies by geographic location and patients’ associated habits. For example, in locations where smokeless tobacco is frequently used, leukoplakia appears with a higher prevalence.Leukoplakia is more frequently found in men, can occur on any mucosal surface, and infrequently causes discomfort or pain (Figure 5-26). Leukoplakia usually occurs in adults older than 50 years of age. Prevalence increases rapidly with age, especially for males, and 8% of men older than 70 years of age are affected. Approximately 70% of oral leukoplakia lesions are found on the buccal mucosa, vermilion border of the lower lip, and gingiva. They are less common on the palate, maxillary mucosa, retromolar area, floor of the mouth, and tongue. However, lesions of the tongue and the floor of the mouth account for more than 90% of cases that show dysplasia or carcinoma.

A number of locally acting etiologic agents, including tobacco, alcohol, candidiasis, electrogalvanic reactions, and (possibly) herpes simplex and papillomaviruses, have been implicated as causative factors for leukoplakia. True leukoplakia is most often related to tobacco usage;more than 80% of patients with leukoplakia are smokers. The development of leukoplakia in smokers also depends on dose and on duration of use, as shown by heavier smokers’ having a more frequent incidence of lesions than light smokers. Cessation of smoking often results in partial to total resolution of leukoplakic lesions. Smokeless tobacco is also a well-established etiologic factor for the development of leukoplakia; however, the malignant transformation potential of smokeless tobacco–induced lesions is much lower than that of smoking-induced lesions.

Alcohol consumption alone is not associated with an increased risk of developing leukoplakia, but alcohol is thought to serve as a promoter that exhibits a strong synergistic effect with tobacco, relative to the development of leukoplakia and oral cancer.In addition to tobacco, several other etiologic agents are associated with leukoplakia. Sunlight (specifically, ultraviolet radiation) is well known to be an etiologic factor for the formation of leukoplakia of the vermilion border of the lower lip.Candida albicans is frequently found in histologic sections of leukoplakia and is consistently (60% of cases) identified in nodular leukoplakias but rarely (3%) in homogeneous leukoplakias. The terms “candidal leukoplakia” and “hyperplastic candidiasis” have been used to describe such lesions.

Whether Candida constitutes a cofactor either for excess production of keratin or for dysplastic or malignant transformation is unknown(see previous section on candidiasis). Human papillomavirus (HPV), particularly subtypes HPV-16 and HPV-18, have been identified in some oral leukoplakias. The role of this virus remains questionable, but there is evidence that HPV-16 may be associated with an increased risk of malignant transformation.Of interest, there is some evidence that oral leukoplakia in nonsmokers has a greater risk for malignant transformation than oral leukoplakia in smokers.

Clinical Features

The incidence of leukoplakia varies by geographic location and patients’ associated habits. For example, in locations where smokeless tobacco is frequently used, leukoplakia appears with a higher prevalence.Leukoplakia is more frequently found in men, can occur on any mucosal surface, and infrequently causes discomfort or pain (Figure 5-26). Leukoplakia usually occurs in adults older than 50 years of age. Prevalence increases rapidly with age, especially for males, and 8% of men older than 70 years of age are affected. Approximately 70% of oral leukoplakia lesions are found on the buccal mucosa, vermilion border of the lower lip, and gingiva. They are less common on the palate, maxillary mucosa, retromolar area, floor of the mouth, and tongue. However, lesions of the tongue and the floor of the mouth account for more than 90% of cases that show dysplasia or carcinoma.

Subtypes

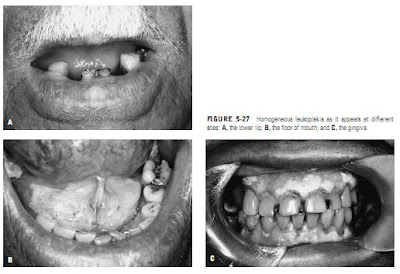

Many varieties of leukoplakia have been identified. “Homogeneous leukoplakia” (or “thick leukoplakia”) refers

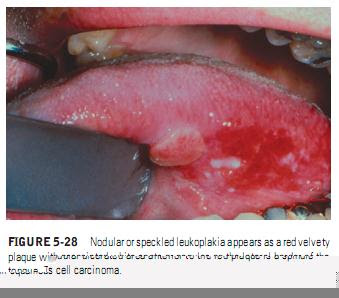

to a usually well-defined white patch, localized or extensive, that is slightly elevated and that has a fissured, wrinkled, or corrugated surface (Figure 5-27). On palpation, these lesions may feel leathery to “dry, or cracked mud-like.”Nodular (speckled) leukoplakia is granular or nonhomogeneous. The name refers to a mixed red-and-white lesion in which keratotic white nodules or patches are distributed over an atrophic erythematous background (Figure 5-28). This type of leukoplakia is associated with a higher malignant transformation rate, with up to two-thirds of the cases in some series showing epithelial dysplasia or carcinoma.“Verrucous leukoplakia” or “verruciform leukoplakia” is a term used to describe the presence of thick white lesions with papillary surfaces in the oral cavity (Figure 5-29). These lesions are usually heavily keratinized and are most often seen in older adults in the sixth to eighth decades of life. Some of these lesions may exhibit an exophytic growth pattern.Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) was first described in 1985.The lesions of this special type of leukoplakia have been described as extensive papillary or verrucoid white plaques that tend to slowly involve multiple mucosal sites in the oral cavity and to inexorably transform into squamous cell carcinomas over a period of many years (Figure 5-30).PVL has a very high risk for transformation to dysplasia, squamous cell carcinomaor verrucous carcinoma (Figure 5-31). Verrucous carcinoma is almost always a slow growing and well-differentiated lesion that seldom metastasizes.

Histopathologic Features

The most important and conclusive method of diagnosing leukoplakic lesions is microscopic examination of an adequate biopsy specimen.Benign forms of leukoplakia are characterized by variable patterns of hyperkeratosis and chronic inflammation. The association between the biochemical process of hyperkeratosis and malignant transformation remains an enigma.

Many varieties of leukoplakia have been identified. “Homogeneous leukoplakia” (or “thick leukoplakia”) refers

to a usually well-defined white patch, localized or extensive, that is slightly elevated and that has a fissured, wrinkled, or corrugated surface (Figure 5-27). On palpation, these lesions may feel leathery to “dry, or cracked mud-like.”Nodular (speckled) leukoplakia is granular or nonhomogeneous. The name refers to a mixed red-and-white lesion in which keratotic white nodules or patches are distributed over an atrophic erythematous background (Figure 5-28). This type of leukoplakia is associated with a higher malignant transformation rate, with up to two-thirds of the cases in some series showing epithelial dysplasia or carcinoma.“Verrucous leukoplakia” or “verruciform leukoplakia” is a term used to describe the presence of thick white lesions with papillary surfaces in the oral cavity (Figure 5-29). These lesions are usually heavily keratinized and are most often seen in older adults in the sixth to eighth decades of life. Some of these lesions may exhibit an exophytic growth pattern.Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) was first described in 1985.The lesions of this special type of leukoplakia have been described as extensive papillary or verrucoid white plaques that tend to slowly involve multiple mucosal sites in the oral cavity and to inexorably transform into squamous cell carcinomas over a period of many years (Figure 5-30).PVL has a very high risk for transformation to dysplasia, squamous cell carcinomaor verrucous carcinoma (Figure 5-31). Verrucous carcinoma is almost always a slow growing and well-differentiated lesion that seldom metastasizes.

Histopathologic Features

The most important and conclusive method of diagnosing leukoplakic lesions is microscopic examination of an adequate biopsy specimen.Benign forms of leukoplakia are characterized by variable patterns of hyperkeratosis and chronic inflammation. The association between the biochemical process of hyperkeratosis and malignant transformation remains an enigma.

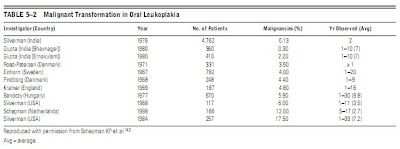

However, the increased risk for malignant transformation and thus “premalignant designation” is documented in Table 5–2.

Waldron and Shafer, in a landmark study of over 3,000 cases of leukoplakia, found that 80% of the lesions represented benign hyperkeratosis (ortho- or parakeratin) with or without a thickened spinous layer (acanthosis).About 17% of the cases were epithelial dysplasias or carcinomas in situ. The dysplastic changes typically begin in the basal and parabasal zones of the epithelium. The higher the extent of epithelial involvement, the higher the grade of dysplasia. Dysplastic alterations of the epithelium are characterized by enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei, cellular and nuclear pleomorphism, premature keratinization of individual cells, an increased nucleocytoplasmic ratio, increased and abnormal mitotic activity, and a generalized loss of cellular polarity and orientation (Figure 5-32). When the entire thickness of the epithelium is involved (“top-to-bottom” change), the term “carcinoma in situ” (CIS) is used. There is no invasion seen in CIS. Only 3% of the leukoplakic lesions examined had evolved into invasive squamous cell carcinomas.Diagnosis and Management

A diagnosis of leukoplakia is made when adequate clinical and histologic examination fails to reveal an alternative diagnosis and when characteristic histopathologic findings for leukoplakia are present. Important clinical criteria include location, appearance, known irritants, and clinical course. Many white lesions can mimic leukoplakia clinically and should be ruled out before a diagnosis of leukoplakia is made. These include lichen planus, lesions caused by cheek biting, frictional keratosis, smokeless tobacco–induced keratosis, nicotinic stomatitis, leukoedema, and white sponge nevus.

Waldron and Shafer, in a landmark study of over 3,000 cases of leukoplakia, found that 80% of the lesions represented benign hyperkeratosis (ortho- or parakeratin) with or without a thickened spinous layer (acanthosis).About 17% of the cases were epithelial dysplasias or carcinomas in situ. The dysplastic changes typically begin in the basal and parabasal zones of the epithelium. The higher the extent of epithelial involvement, the higher the grade of dysplasia. Dysplastic alterations of the epithelium are characterized by enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei, cellular and nuclear pleomorphism, premature keratinization of individual cells, an increased nucleocytoplasmic ratio, increased and abnormal mitotic activity, and a generalized loss of cellular polarity and orientation (Figure 5-32). When the entire thickness of the epithelium is involved (“top-to-bottom” change), the term “carcinoma in situ” (CIS) is used. There is no invasion seen in CIS. Only 3% of the leukoplakic lesions examined had evolved into invasive squamous cell carcinomas.Diagnosis and Management

A diagnosis of leukoplakia is made when adequate clinical and histologic examination fails to reveal an alternative diagnosis and when characteristic histopathologic findings for leukoplakia are present. Important clinical criteria include location, appearance, known irritants, and clinical course. Many white lesions can mimic leukoplakia clinically and should be ruled out before a diagnosis of leukoplakia is made. These include lichen planus, lesions caused by cheek biting, frictional keratosis, smokeless tobacco–induced keratosis, nicotinic stomatitis, leukoedema, and white sponge nevus.

If a leukoplakic lesion disappears spontaneously or through the elimination of an irritant, no further testing is indicated.For the persistent lesion, however, the definitive diagnosis is established by tissue biopsy. Adjunctive methods such as vital staining with toluidine blue and cytobrush techniques are helpful in accelerating the biopsy and/or selecting the most appropriate spot at which to perform the biopsy.

Toluidine blue staining uses a 1% aqueous solution of the dye that is decolorized with 1% acetic acid. The dye binds to dysplastic and malignant epithelial cells with a high degree of accuracy.The cytobrush technique uses a brush with firm bristles that obtain individual cells from the full thickness of the stratified squamous epithelium; this technique is significantly more accurate than other cytologic techniques used in the oral cavity.It must be remembered that staining and cytobrush techniques are adjuncts and not substitutes for an incisional biopsy. When a biopsy has been performed and the lesion has not been subsequently removed, another biopsy is recommended if and when changes in signs or symptoms occur.

Toluidine blue staining uses a 1% aqueous solution of the dye that is decolorized with 1% acetic acid. The dye binds to dysplastic and malignant epithelial cells with a high degree of accuracy.The cytobrush technique uses a brush with firm bristles that obtain individual cells from the full thickness of the stratified squamous epithelium; this technique is significantly more accurate than other cytologic techniques used in the oral cavity.It must be remembered that staining and cytobrush techniques are adjuncts and not substitutes for an incisional biopsy. When a biopsy has been performed and the lesion has not been subsequently removed, another biopsy is recommended if and when changes in signs or symptoms occur.

Definitive treatment involves surgical excision although cryosurgery and laser ablation are often preferred because of their precision and rapid healing.Total excision is aggressively recommended when microscopic dysplasia is identified, particularly if the dysplasia is classified as severe or moderate. Most leukoplakias incur a low risk for malignant transformation. Following attempts at removal, recurrences appear when either the margins of excision are inadequate or the causative factor or habit is continued. In any event, such patients must be observed periodically because of the risk of eventual malignancy.

The use of antioxidant nutrients and vitamins have not been reproducibly effective in management. Programs have included single and combination dosages of vitamins A, C, and E; beta carotene; analogues of vitamin A; and diets that are high in antioxidants and cell growth suppressor proteins (fruits and vegetables).

PrognosisAfter surgical removal, long-term monitoring of the lesion site is important since recurrences are frequent and because additional leukoplakias may develop.In one recent series of these lesions, the recurrence rate after 3.9 years was 20%.

Smaller benign lesions that do not demonstrate dysplasia should be excised since the chance of malignant transformation is 4 to 6%.For larger lesions with no evidence of dysplasia on biopsy, there is a choice between removal of the remaining lesion and follow-up evaluation, with or without local medication.Repeated follow-up visits and biopsies are essential, particularly when the complete elimination of irritants is not likely to be achieved. In such cases, total removal is strongly advisable. Follow-up studies have demonstrated that carcinomatous transformation usually occurs 2 to 4 years after the onset of leukoplakia but that it may occur within months or after decades.

Each clinical appearance or phase of leukoplakia has a different potential for malignant transformation. Speckled leukoplakia carries the highest average transformation potential, followed by verrucous leukoplakia; homogeneous leukoplakia carries the lowest risk. For dysplastic leukoplakia, the clinician must consider the histologic grade when planning treatment and follow-up. In general, the greater the degree of dysplasia, the greater the potential for malignant change. In addition, multiple factors play a role in determining the optimum management procedure. These factors include the persistence of the lesion over many years, the development of leukoplakia in a nonsmoker, and the lesion’s occurrence on high-risk areas such as the floor of the mouth, the soft palate, the oropharynx, or the ventral surface of the tongue.

The use of antioxidant nutrients and vitamins have not been reproducibly effective in management. Programs have included single and combination dosages of vitamins A, C, and E; beta carotene; analogues of vitamin A; and diets that are high in antioxidants and cell growth suppressor proteins (fruits and vegetables).

PrognosisAfter surgical removal, long-term monitoring of the lesion site is important since recurrences are frequent and because additional leukoplakias may develop.In one recent series of these lesions, the recurrence rate after 3.9 years was 20%.

Smaller benign lesions that do not demonstrate dysplasia should be excised since the chance of malignant transformation is 4 to 6%.For larger lesions with no evidence of dysplasia on biopsy, there is a choice between removal of the remaining lesion and follow-up evaluation, with or without local medication.Repeated follow-up visits and biopsies are essential, particularly when the complete elimination of irritants is not likely to be achieved. In such cases, total removal is strongly advisable. Follow-up studies have demonstrated that carcinomatous transformation usually occurs 2 to 4 years after the onset of leukoplakia but that it may occur within months or after decades.

Each clinical appearance or phase of leukoplakia has a different potential for malignant transformation. Speckled leukoplakia carries the highest average transformation potential, followed by verrucous leukoplakia; homogeneous leukoplakia carries the lowest risk. For dysplastic leukoplakia, the clinician must consider the histologic grade when planning treatment and follow-up. In general, the greater the degree of dysplasia, the greater the potential for malignant change. In addition, multiple factors play a role in determining the optimum management procedure. These factors include the persistence of the lesion over many years, the development of leukoplakia in a nonsmoker, and the lesion’s occurrence on high-risk areas such as the floor of the mouth, the soft palate, the oropharynx, or the ventral surface of the tongue.